MLK's Final And Most "Dangerous" Message to America Transcended Race

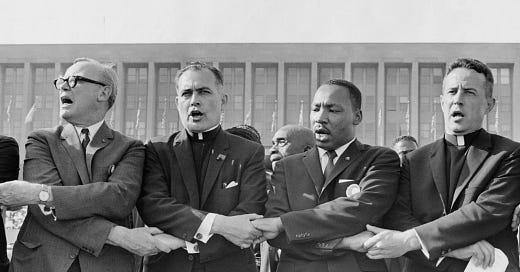

Walking the final leg on the road to equality will require black people to unite with others against a common threat

“[Martin] spoke out sharply for all the poor in all their hues,

for he knew if color made them different,

misery and oppression made them the same.”

— Coretta Scott King

When I was a young girl growing up in the 70s, Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy was everywhere — on schools and boulevards, in hospitals and museums, on postage stamps and t-shirts. He was synonymous with civil rights and was a cornerstone in school textbooks, and it was almost impossible to discuss race relations without invoking King’s name.

Today? Not so much.

The names we now associate with the struggle for racial equality are Trayvon Martin. Ferguson. Black Lives Matter. Freddie Gray. The icon who led the effort to revolutionize our social and political landscape by ending segregation almost never surfaces in our racial dialogue. We may think about him briefly if our employer gifts us a day off work, or if we happen to catch a 10-minute retrospective on CNN. We remember his legacy, we honor what he accomplished, and we lament his untimely death. But when racial drama inevitably dominates the news cycle again, we never hear King’s peaceful message of unity and harmony; instead, we’re besieged by anger and vitriol. What we hear doesn’t bring us together. If anything, it drives us further apart.

King gave his life to set us on the path to a better world and pointed us in the right direction, but somehow, we’ve strayed off course. We’ve lost our way. Now more than ever, we need to remember not only what King did, but also take to heart the guidance he left us for moving forward.

The United States is a nation in crisis.

We face a renewed, seemingly insurmountable problem with race and sit on the precipice of a gaping divide wider than any we’ve seen in decades. Our leaders and our media are doing little, if anything, to help us bridge this gap. In many ways, they seem to be making it worse. Yet this gaping divide isn’t a problem that belongs solely to black America or white America. Ultimately, this racial wedge is an American problem because it keeps us from seeing a looming existential threat that endangers all of us.

Shortly before he died, King sequestered himself in Jamaica to write a book that few have even heard of, aptly titled Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos Or Community? In this prophetic guide, he shared a final epiphany that pundits and social justice commentators never mention now: the struggle for racial quality can’t move to the next phase until we achieve equality on a level that transcends race. In other words, the ongoing struggle must be one of human equality.

I think we can still fulfill King’s dream of a better world, but first we’ll need to do something that few of us seem willing to attempt, especially if we’re black: we’ll need to release our anger.

This is a tall order in our current culture of outrage. Today, we’re angered by anything and everything, convinced that yelling at the “other” side is the only way to save a country that’s plunging over a cliff. But black outrage burns brightest, with the intensity of a bonfire. The flames never die because there’s no shortage of emotional kindling: childhood traumas, photos of ancestors in chains and hanging from trees, videos of police beatings, indignities suffered at restaurants, callous remarks caught on hot mics, and a media that constantly tells us how much our president hates us. Everywhere we turn, we’re reminded that white America is our enemy.

We channel our outrage into online diatribes seething with thinly-veiled contempt for white people. Medium articles like The Unbearable Whiteness Of (fill in the blank). Tricked By Whiteness. I Don’t Need Gun Control Laws, I Need White People Laws. White People, You Ain’t Shit…

It’s an anger I know all too well; the anger of feeling that despite the progress we’ve made, we’re still not living in the world we deserve to live in; that while many of our problems have been solved, many more remain. An anger that comes from looking through the windshield, lamenting how much further we have to go on the road ahead, not glancing in the rearview mirror to see how far we’ve come.

I’ve lived with this quiet rage inside me for most of my life, but as I’ve grown older I’ve come to realize that my anger, while understandable and inevitable, can be self-defeating. When we’re gripped by anger, we can’t move forward because we’re too focused on the past. We become so fixated on injustices we’ve suffered that we don’t appreciate the roadblocks we’ve overcome.

Our anger keeps us plugged into a distorted reality where we see our allies as enemies.

King emphasized the need to release our ancestral anger and acknowledge the progress we’ve made towards our ultimate goal. In the wake of the Voting Rights Act in 1965, black Americans struggled with the grim reality of having achieved constitutional rights that looked good on paper, but didn’t sync with the world they lived in. King faced a dispirited and disenchanted community that was anxious for deeper and more meaningful changes. Many feared that the struggle had failed and all hope was lost.

In Where Do We Go From Here, King cautioned his followers against “unjustified pessimism and despair,” reminding them that a “final triumph is the accumulation of many short term encounters” and that success should not be judged by the failure to immediately achieve a “full victory.” While the movement hadn’t leveled the playing field, racism was clearly no longer “the salient fact” of the black experience. If he were with us today, I think King would also encourage us to release our anger because it blinds us to the true source of our suffering. Anger keeps us plugged into a distorted reality where we see potential allies as enemies. Anger keeps us ignorant to the fact that the targets of our outrage increasingly find themselves victims of the same threat we’ve faced for generations.

As he wrestled with the next steps for a restless movement, King admonished his followers to remember something that many today — trapped in the culture of outrage — have forgotten: the civil rights movement wasn’t a unilateral effort. The black community could not have moved the government to institute sweeping legislation “without the weight of the aroused conscience of white America.” He cautioned against the temptation to alienate these allies with bitter slogans and rhetoric: "There is no solution for [blacks] through isolation,” King argued, because they can’t walk the remaining distance on the road to equality alone.

King knew these strategic alliances would be critical in the future because he had identified a danger that he believed was greater than racial inequality: economic inequality. While it was clear that the root of black misery was “pervasive and persistent economic want,” it was also undeniable that blacks were no longer the only ones suffering from economic disadvantage.

He could see a common struggle emerging in black and white America, and he realized that there could be no genuine progress for blacks “unless the whole of American society takes a new turn toward greater economic justice.” Because there were more poor white Americans than poor black Americans, he reasoned that “[t]heir need for a war on poverty [was] no less desperate,” and they would also “benefit equally [with blacks] in the achievement of social progress.” United in their common struggle, they stood a better chance of victory.

There can be no genuine progress for blacks “unless the whole of American society takes a new turn toward greater economic justice.”

Fifty years later, the common struggle that black and white America face has intensified. In 2016, the percentage of white children living with a single parent was almost 30%, more than twice as high as the percentage in 1990, and more than the percentage of black children living with a single parent in 1960. The gap between the unemployment rate for blacks and whites has narrowed to just 3%. While mortality rates for blacks and Latinos have declined significantly, white men are dying in larger numbers than any other demographic due to drugs, suicide, depression, and inability to work. In other words, the gap between black misery and white misery is narrowing.

Decades ago, King saw the approaching class tsunami that has now hit shore and is sweeping working class whites into a heap of social debris along with blacks, Latinos, and other people of color. Where Do We Go From Here was King’s last, desperate attempt to convey the urgent need to forge alliances among these marginalized groups in the quest for human equality. It was a prescient warning to black America and white America to unite against the looming threat we would all soon face: a class war waged by the very few with real privilege and power against the rest of us. And it’s a threat that’s now gone parabolic.

Today, the inequality gap in the U.S. has returned to levels not seen since the Great Depression:

The household wealth owned by the top 0.1 percent — 160,000 families in the U.S. — has increased from 7% in the late 1970s to 22 percent in 2012.

The 400 richest Americans now own more wealth than the bottom 150 million.

Wealth inequality in some American cities is now more extreme than in Mexico and Chile.

At the current pace, the richest 1% will own two-thirds of all global wealth by 2030.

Just as King warned, race is no longer our biggest problem; we’re locked in an undeclared class war, and we’re losing — badly. But instead of mobilizing against a predatory System that elites have armed themselves with, we’re raging against those sitting in the trenches beside us. In our despair, we’re lashing out at people we believe have “more” privilege in a collapsing economy. We’re blindly attacking potential allies who are equally defenseless.

“[S]omething is wrong with the economic system of our nation.”

As he plotted a way forward, King began to push the envelope further by boldly questioning why there were 25 million poor people living in the richest country in the world (NOTE: by 2017, the number of people living at or below the poverty level in the U.S. would balloon to 58.3 million, i.e. nearly 20% of the U.S. population). He knew he was treading “on dangerous ground” because he was effectively saying that “something is wrong with the economic system of our nation.” According to author David Garrow, King understood that carrying this “new” message to America made him a “far greater political threat” to the U.S. government than he had previously posed as an advocate for racial equality. His colleague, Walter Fauntroy, was with him the day President John F. Kennedy was assassinated and recalled King gazing out the window and musing: “Walter, you know, if they’ll kill a president, I won’t live to be 40.” Not fearing death, he pressed on.

he National Welfare Rights Organization marching to end hunger as part of the Poor People’s Campaign, 1968. Jack Rottier photograph collection, George Mason University Libraries.

Most Americans don’t know that in the final months of his life, King was planning something truly revolutionary. In November 1967, he met with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to launch a Poor People’s Campaign aimed at finding solutions to the fundamental problems facing the country’s poor. King planned to lead the Poor People’s March on Washington, D.C. in May 1968 — a broad, multiracial alliance of blacks, working class whites, Asians, Latinos, and Native Americans focused on reducing poverty for all, irrespective of race. It would have been an unprecedented display of unity against a failing economic System.

On April 4, 1968, less than one month before the Poor People’s March was scheduled to take place, King was assassinated at the age of 39.

We’ll never know where King’s multiracial alliance would have eventually taken us. We’ll never know how much further along the road to wealth and human equality we would be had he dodged an assassin’s bullet. That muggy spring evening in Memphis, America lost its most fearless and outspoken voice for fundamental, systemic change. And from that point on, we’ve drifted off-course.

Without a leader, we’re not entirely lost. But it’s up to us to find our way back. I think we can do it, but only if we move forward together. I also think the black community will be critical in this effort, since our voice often rings loudest in discussions of equality.

But first, we’ll need to unplug from a reality that’s kept us tethered to old wounds. We’ll need to set aside our anger and join hands with those who suffer beside us, without our awareness. We’ll need to understand that relentlessly lashing out at others for wrongs we’ve suffered and still endure may feel cathartic, but it won’t win us allies we need to continue our fight. We’ll need to acknowledge that the root cause of our anguish is no longer racism, but an economic system that increasingly devalues and demeans all human life.

So when we honor King today, let’s do more than just remember what he accomplished and how he died. Let’s commit to following his final guidance for moving forward together as one people and one tribe. Because something huge — seismic, in fact — is unfolding around us, and we’d better wake up and pay attention. It's time to stop fighting each other and link arms before the ground beneath us gives way and swallows us all.

“The only thing necessary to bring people out of poverty is for others to become rich at a slower pace.”

— Martin Luther King Jr.